- Home

- Victoria Andre King

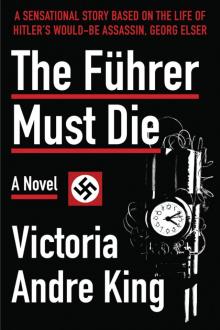

The Führer Must Die

The Führer Must Die Read online

Copyright © 2016 by Victoria Andre King

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Yucca Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Yucca Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Yucca Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Yucca Publishing® is an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.yuccapub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Jacket photo: Dreamstime/Fernando Gregory

Print ISBN: 978-1-63158-104-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63158-110-6

Printed in the United States of America

To Don,

I owe you a tombstone and I wish you were here.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

A storyteller is under a different kind of obligation than a historian. Usually, history expresses the folly of the victors.

Politics, on the other hand, expresses the unrequited desires of the insatiable.

A historian is supposed to tell what they can prove actually happened. A storyteller tells what should have happened or what might have happened. But, a story is a story nonetheless an inevitably subjective account of what happened to somebody sometime…

I hope you enjoy it, but cannot guarantee any particular outcome or conclusion.

—Victoria

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Some stories just get under your skin. Some individuals are remarkable precisely because, although they appear quite ordinary, they prove to be capable of extraordinary things. Georg Elser was just such an extraordinary, ordinary, man… as was Donald Schwarz.

I would like to extend special thanks to the librarians at the East 67th Street and Webster (York Ave.) branches of the New York Public Library (Don’s home away from home where the lion’s share of the research was done). They had the patience and tenacity to deal with my dear friend’s changeable demeanor.

Also I extend many thanks to Peter & Sandra Riva for their valuable assistance throughout the arduous process of editing tweaking and finally getting this work out there.

I owe so much to my husband, Aristophanes Kondos. Not only did he understand and encourage Don’s and my inexplicable yet bizarrely creative friendship, he also encouraged me when my confidence was at its nadir and supported my insanity even when that resulted in privations.

Lastly two great books by two great historians:

THE FUHRER AND THE PEOPLE

by

J. P. Stern.

and

HITLER’S PERSONAL SECURITY

by

Peter Hoffmann

NOVEMBER 8TH, 1939

THE STIFF SUSPENSION OF THE R-35 motorbike jolted the spine of the Corporal astride it at every rut along the empty Munich streets. The dense fog caused the light to bubble around the street lamps and had filled the Corporal’s goggles with sooty smears. He had tried negotiating his way without them but the gooey air had caused his eyes to sting. The limited visibility had made his progress frustratingly slow so he perked up a bit when the illuminated entrance of the BürgerBräuKeller came into view … that was until he recalled why he was going there.

---

Meanwhile, at a forlorn border crossing, two guards sat playing cards and taking turns glancing out the windows while they waited for the Führer’s speech to begin. The particular crossing was on the outskirts of a sleepy berg called Konstanz located at the tip of a promontory, which, if seen from the air, resembled the scrotum of Germany nudging the northern border of Switzerland. It was banked on either side by two bodies of water: the smaller Untersee to the west, and the Obersee Bodensee to the east and south. It was never quite clear to which country the bodies of water rightfully belonged and as such was one of those unnatural borders that should have led to war long before as had happened in Danzig, the problem with Konstanz was that no one was interested. That inevitably made it the best possible place to sneak out of Germany.

The city’s economic ties were with Switzerland and most of the locals had been commuting across the border for the greater part of their adult lives. In the ’20s Konstanz had been a tourist trap, but by 1939 the tourists were gone and the only available jobs were in the towns that ringed Basel and Zurich. People commuted to work during the day or to their lovers at night or smuggled undisturbed. The traffic was too heavy for customs checks to be more than random. Even the border police had lost interest.

The night of November 8th however was unusually cold and traffic had died off before 9:00 p.m. The night was very black and white. No snow had fallen yet, but the moon was close to full and the pine and fir trees on the hills stood out blacker than the sky, sucking up the light around them. The thin wind off the lakes had given up once the temperature had shifted and the branches of the fir trees hung down heavily in the cold, wet air waiting to freeze.

---

Back in Munich SS officer Christian Weber, the Führer’s chief of security for the event, listened without expression as the Corporal relayed the message. Yet another change in the program … this particular appearance had come to resemble one of those British drawing room comedies, the sort of theatre that was utterly incomprehensible to a practical people like the Germans. Weber was secretly elated at the prospect of the evening’s activities winding down early and thus the weight of the entourage leaving his shoulders and returning to Berlin, but he had a solemn duty to show his underling that he was inconvenienced, lest the chain of command be threatened. Personally he found the “Old Guard” a tiresome “pride” of toothless lions, to whom the only pleasure that remained was hearing themselves roar. There were times when the amount of sentimentality that permeated the Reich baffled him, but alas… orders were orders.

---

Outside Konstanz the night was almost dead. The only movement was a solitary man walking through the trees moving relentlessly toward the Swiss border. Georg Elser was so completely ordinary that he was difficult to describe. There was no feature or gesture that summed him up. There was a strange lack of anything personal; even his women had always had trouble remembering what he looked like. Men rarely ever noticed him at all and that was the only reason he was still alive. He was of less than average height and very thin, swallowed up in a cheap black overcoat. With the moonlight full in his face his eyes shimmered like silver.

One hundred meters from the border he gave up any attempt at concealment and walked dreamily toward Switzerland. He was unarmed. He’d heard that in America every worker carried a weapon, but that was because in America work had a quality of adventure to it, a sense that all possibilities were open. In Germany they weren’t; work was just boring and hopeless and you lived your life without interest, like it was a dead-end civil service job.

---

Back in Munich, Weber approached the entourage. He scanned the faces, searching for the next appropriate link in the chain of command, and speculated as to who they would finally appoint to inform the Führer at the podium. The din seemed to be nearing crescendo, that shrill voice reaching a feverish pitch while enthusiastic bellows emitted from the hall below. Weber dutifully singled out his immediate superior and passed the “hot potato” on.

---

Georg flexed his hands in his pocke

ts, the thick tendons creaking in the cold; he was reminded of his strength and comforted by it. In the thin coat he hunched his shoulders against the cold and the darkness gave him the deformed shape of a factory worker: shoulders narrow, face unnaturally large, torso scrawny yet muscular as a chimpanzee’s with the thick overdeveloped forearms of a carpenter. When he worked they swelled up to twice their size and the thick blue rubbery veins stood out hard as bone. Inside pockets, his hands were clenched against the cold, the fingers pressed to the palms and the hands pressed against his body the way a young child would hold them. Outside of the childish awkwardness there wasn’t much to him, he was hardly there at all—the reason women had often found him attractive. He was like the faceless, strictly functional male figure in a feminine fantasy and women were able fit him into their current daydream without the slightest difficulty.

The sound of Hitler’s voice pummeled its way into his consciousness. The Führer was working himself into a rage fit and somewhere in his subconscious Georg realised that he wasn’t imagining it … he was actually hearing it, but he still didn’t pay any notice.

At the border crossing the two guards were now smoking and watching the checkpoint from the open window of their post which, as the sign said, had once been a school for “Defective Children.” They listened to the insect drone of Hitler’s voice coming from their radio and the Austrian accent was murderous, you had to listen carefully to understand what was being said and the radio was turned up so loud that you couldn’t tell the static from that screaming, scratchy voice. Georg heard it as clearly as the guards saw him, but it didn’t register; it was indistinguishable from the other voices raging inside his head.

So, as he reached the checkpoint, the two guards seemed to appear out of nowhere and cut off his escape front and back. …

“Papiere, bitte!”

Papers, please … the one essential German phrase. The guards seemed more disgruntled than anything else, aggravated at having had to leave the comparative warmth of their post. Georg handed his papers over and smiled.

“Johann Georg Elser …,” said the guard who was holding his papers, “… your travel permit is five years out of date.”

“My apologies, I should have had it renewed.”

He smiled again as he said it and the guards, not being complicated men, thought as clearly as if it had been written in cartoon balloons over their heads. … “He’s harmless so we should just let him pass.” The best way to deal with a breach of routine since the dawn of time has always been to ignore it, and Georg was helping them with his innocent smile. But the guards were annoyed by the need to make a decision. Clearly, he was not a deserter so the simplest thing would be to let him go. He’d be let go anyway and there would be a stack of paperwork to make out in quintuplicate and all for nothing. …

But then, they noticed that he had no luggage. You do not travel to a foreign country, even one so close, without luggage, without even a tooth brush or a tool box. Again the balloons as they thought: “He’s a young man so perhaps he’s visiting his girlfriend!” So, one of the guards gave him a meaningful look.

“Purpose of visit?”

But Georg remained silent. He had never actually given it any thought so he actually had no idea. Spontaneous improvisation was not in his nature, and it had never occurred to him to rehearse something he had done so many times in the past.

“This is a routine inquiry…” said the guard holding his papers, “… but since your papers are not in order, we must conduct a body search.”

Georg put his hands on top of his head and smiled again, but the guards had stopped watching his face. Their search was as slovenly as his attempt to cross the border. They were violating standard procedure. One searched him while the other stood looking over his colleague’s shoulder with polite interest. That man should have been at a distance of five meters, covering Georg with a pistol in case he attempted to run, but they seemed to be inviting him to try or, maybe they were just sure he wouldn’t.

The guards found nothing sinister, but what they did find was irritatingly pointless: some finely machined pieces of shiny metal, a dog-eared copy of Brecht’s Die Dreigroschenoper or “The Threepenny Opera” with the name Celia Peachum scribbled across the top and a souvenir postcard from the BürgerBräuKeller, a beer hall in Munich. To complicate things further, the postcard showed the Führer speaking in the ballroom, face contorted, sawing at the air with fists clenched in rage between two rapt looking nerds with Hitler mustaches; a strange thing for a man trying to slink his way out of the country to be carrying. Clearly, as noted, the man was not a deserter. But no luggage and no girlfriend, that was very irregular and the guards did not like irregularities. Finally, they walked back into the school house for defective children and called for a Polizei-Kubelwagen to take him back to Konstanz, five kilometers from their post. They didn’t say what to charge him with, that was never a problem as there were plenty of unsolved crimes in search of culprits.

Georg was driven back to Konstanz by one tired, old cop who kept him handcuffed in the front seat and didn’t ask any questions. Being a police car, the kubelwagen had a radio. It was tuned to the Führer’s broadcast; it had to be, it was on every station and the Führer raved on and on, chanting himself into a trance. He’d been talking for almost an hour and by now the staccato delivery was so fast that the words were unintelligible. It didn’t matter, the bright giddy meaning was clear and the crowd clapped and stamped and shouted.

The Führer was still at it when the cop put Georg in a detention cell and began to itemize his belongings on a wooden table of an indeterminate color. The cop noted them down carefully as if he were signing a peace treaty, bearing down on the pencil to mark his way through all four carbons. The radio was still tuned to the Führer’s speech, but it wasn’t clear if it was Hitler or some party hack, they all sounded alike anymore. The same kind of hoarse grating voice straining beyond its range, the voice breaking then coughing itself clear and then starting again with a whoop and a shriek, rampant.

The cop’s brows furrowed as he read the title of the play and he hissed between his teeth, “Entartete kunst …”—degenerate art. Then he came to the postcard from the BürgerBräuKeller. His shoulder badge announced that he was an Anwarter, an apprentice patrolman, though he looked like he was over seventy. All the able-bodied men were in the SS, preparing to defend the world from civilization. The “leftover” Anwarter glared at Georg suspiciously.

“Right now, at this very moment we are listening to the Führer speak from the BürgerBräuKeller.”

The radio made a bang and a shrieking whistle and then went dead silent. The Anwarter looked at Georg with his face out of gear, as if he were asking himself a vague question. Georg gave him his most beautiful smile and said, “The applause sounded almost like an explosion.”

---

The BürgerBräuKeller in Munich was a 300-year-old structure that had been built to last 100 years. It half supported the buildings leaning against it like a group of drunks that somehow managed to prop each other up. Under the force of the explosion the building swayed and shifted, trying to find a new point of balance. The gas lines to the kitchen had ruptured and were blowing flames into the ballroom. The ancient wood, dry as paper, was burning out of control and the stamped tin ceiling had come down like a massive fly swatter.

Within minutes the street outside was crawling with firemen and police. Access should have been easy because parts of the walls had blown out, but the tin ceiling was too big and wedged too tightly to be moved and they had no tools except the usual fire brigade axes and pry bars. An acetylene torch was suggested but, even if one could have been found, it would have cooked the wounded trapped underneath. Tin snips were suggested, but it would have taken hours to cut the ceiling into manageable pieces and they had minutes at best. Those who had thought to bring the manual rapidly thumbed through it to make sure they were following the authorized procedure for the situation, only to find th

at the manual did not cover such a situation. There were no rules to guide them, they were entirely on their own and would be judged by the success or failure of their decisions. It was completely unfair and absolutely terrifying. Someone suggested propping up the ceiling, but that would have required heavy machinery and they didn’t have that either. Police, SS, SD, Gestapo, and Nazi party officials were in tight groups and shouting at each other. No one was listening, not even to themselves; it wasn’t communication. The shouting seemed to serve some other utterly egoistic function for self preservation.

Each of the distinct interest groups represented had its own hierarchy. Distinguished-looking gentlemen were clinging desperately to procedure in an attempt to disguise their own terror while simultaneously trying to bully their underlings into taking as much responsibility as possible. It could be said that the stiffer the upper lip, the greater the sense of imminent doom. By far the stiffest upper lip on site belonged to Baron Karl von Eberstein, Munich Polizei Prasident, whose unenviable responsibility it had been to oversee security—albeit unofficially—for the Führer’s appearance. The “official” responsibility had belonged to SS officer Christian Weber, who no one could locate at the moment and who, as such things usually went, would probably never be seen or heard from again.

Over the years, von Eberstein’s title had afforded him certain privileges and a diverse social circle; however, it could by no means shield him from political fallout. To keep himself from becoming the Gestapo poster boy, he had to provide them another alternative immediately, and the shoe would have to fit more perfectly than Cinderella’s. He scanned the various huddles of authority seeking out an ally; if not an actual ally then at least someone he could intimidate or manipulate sufficiently to save himself. The chosen would have to be high enough on the food chain to be effective, yet not high enough to sell Eberstein out to save their own future.

Artur Nebe had initially chosen a career in criminal investigation because he found it pleasantly diverting. It was one of few fields in which you could work as an individual, yet have access to functionaries who could relieve you of tedious errands. The political changes of the last few years had become more and more troubling. Anytime you looked over your shoulder somebody was always staring back, somebody who of course also had somebody else looking over their shoulder and so on. Personal loyalty and professional loyalty had given way to party loyalty, which basically meant you couldn’t trust anybody anymore. Nebe gazed over the beer hall wreckage grimly. Whatever the motive had been, the result was purely political and would be exploited as such, serving the perfect pretext for nervous party climbers—people whose only insurance was the obliteration of all competence in the ranks below them. In five days, he would be forty-five years old; too old and too poor to enjoy life in exile, yet too young for any hope of retirement. Amidst the rubble he spotted his personal functionaries dutifully collecting physical evidence, photographs, and measurements, and he wondered for how long they could be counted on even for that.

The Führer Must Die

The Führer Must Die